Noah Kadner: Alex Proyas is an Australian film director, screenwriter, and producer. He’s best known for directing films like The Crow, Dark City, I Robot, Knowing, and Gods of Egypt. A longtime master of visual effects wizardry, Proyas is currently in pre-production on a horror movie to be shot in an LED volume. His love of filmmaking and visual effects happened at an early age.

Alex Proyas: My father took me to 2001: A Space Odyssey, a rerelease. So, to say, I was, but I was still really young. I was like six years old or something. And it just blew my mind. He had no idea what the hell film was, and nor did I, and I kept asking him questions what did it mean?

And he couldn’t work it out. But, what a film. blow a young person’s brainwave I didn’t walk out going, I’m going to be a filmmaker, but I was like, wow, what an amazing world I’ve just been immersed in, it felt like I’ve been to space as a result of that. Film. And I think I probably thought, okay, great. I’m going to be an astronaut now. I think that’s probably what I decided at that point. But then, over the next few years, I went more and more, going to see movies.

And I just more and more realized that’s what I wanted to do. And So I convinced my parents to buy me a super eight. For a birthday or something. And at the age of 10, I started making films, and I think I pretty much knew at that point that’s what I wanted to do. So then I had to do anything else now. So I’m stuck with it,

Noah Kadner: Proyas attended film school in Australia and ultimately discovered a talent beyond traditional filmmaking.

Alex Proyas: At that stage, I actually wanted to be an animator, which is why I ended up for an animation company.

They gave me a job in the days when it was cels. Clear shape cels that they draw the animation on. my job was to clean the cells. They put them through the Xerox machine, and they come out all smudgy, and you’d have to clean them to finesse the lines of the animation that the animated had drawn.

So that was a great job I had for about two months as I applied for film school. And I, fortunately, got in, I actually lied about my age. They wouldn’t accept you if you were under 18, and I actually managed to get in at the age of 17,

Noah Kadner: Proyas worked away at animation for a time but soon found himself looking for additional avenues of expression with like-minded individuals.

Alex Proyas: I formed a company with a couple of other film school students that I was at film school with. Because in Australia, There wasn’t much to offer in the industry. You would either go and work at a TV station or something, it wasn’t like there was a clear path To being a filmmaker as there is in the industry and Hollywood, so there wasn’t a lot of very inspiring work being done at that stage in Australia. the films were. Very hit and miss.

And we decided to take out destiny into our own hands And, we had a lot of friends in bands. This was like the early eighties, and everyone was in a band, and in Australia that, the medium was booming. There was a great live music industry, and all the pub bands would be playing in all the pubs, and that’s where a lot of the great Aussie bands came out of, period, and we thought, let’s make music videos, MTV was happening and. It seemed a way we could actually earn our keep do some creative stuff. And it worked out for us quite well. we started off with friends in bands and doing them for whatever money.

Their parents would give us to make a music video, a couple of hundred bucks to Boston film, stock, and stuff. Eventually developed to like, I ended up going to LA and making, music videos for very high-profile international act.

Noah Kadner: Given his success as a music video director, Proyas looked to longer forms of filmmaking initially in the indie world.

Alex Proyas: I already made a feature film, a film called Spirits, which we made on a very low budget in Australia. and that came about actually through the music industry. we’d done some music videos for INXS. And then management, wanting to get to work on movies, develop movies, primarily for Michael Hutchence, who was the lead singer of INXS who was, starting to move into the acting field and was acting in some movies, so they’re very keen to work with, more filmmakers, to make vehicles, for Michael specifically. , and so I had this, 45-minute long short film, I’d made a bunch of shorts by this stage, and it was my stepping. Towards my first feature. and there, the inaccessible management read the script and said, great, fantastic. Michael would be great for this. And I went great. I think he’s terrific, and I’d already worked with him, so I knew him.

And there was a particular character in that story that really would have worked great for Michael. but the funny thing was that management didn’t really know much about the film, so they read this 45-page script and assumed it was. and I hate to explain to them no, that it’s not a feature features are usually around, about a hundred pages or more, a minute per page kind of thing, and they basically said. Can you turn it into a feature? And I said, sure. Give me a week. It’ll become a feature, which is effectively what I did. I just added some stuff, and we ended up with a feature, but ironically, Michael didn’t end up being in the movie because, Period between them being interested in us and actually being able to start shooting, the band had reached incredible levels of success, and they are too busy playing Wembley stadium and whatever the hell they were doing at the time, but we still got to make the film, and partly financed by the band themselves, through their management.

Noah Kadner: With his mastery of visual effects and directing, Proyas came to the attention of Hollywood and was offered a major comic-book superhero property at a time when there were few in theaters: The Crow.

Alex Proyas: The first digital effect I ever did was in The Crow, and we actually did a couple of shots in The Crow on a Mac plus or something was like one of the very first Macs. And I remember doing this one shot of the character running along the rooftops, and we put in some rain or something, we did it digitally.

And that was the very first time I’d ever experienced doing digital work; It was done at NTSC resolution. And it ended up being on a big screen, but because there was a lot of rain and stuff, and I wanted a sort of distress look anyway and got away with it, for me VFX was second nature because of my experience making music, videos, and commercials, and we were already doing that stuff. We were doing visual effects in a digital space I’ve always been about world-building too, as a filmmaker because of that 2001 experience, I think, so to me, I very easily go that area.

So it felt very organic to me. I couldn’t wait for it to improve and become more streamlined than we are now. And I think. Photography allowed us to get that final bit of streamlined quality there. I’d worked at one of the first red cameras because I would test all the cameras, every film that came along.

Lucas started using digital cameras in the Star Wars prequel trilogy. I kept testing the cameras to see what they were like. And I remember testing those particular cameras, which I think were Sony cameras.

And they were like 1080P or something, those cameras thinking, no, I don’t. Use this stuff, it’s just not good enough to put on the big screen, but when the first RED camera came along, I thought, finally, here we are. We’ve got something that I was really excited about it.

And I was doing a lot of still photography/ digital photography at the time. And finally, I saw a moving version of what I was doing. I thought it was great. And you had great control with it was everything I wanted it to be. And then, of course, the pipeline from photography to completion through VFX and post-production becomes a much cleaner way to work. I think if you’re in that digital realm,

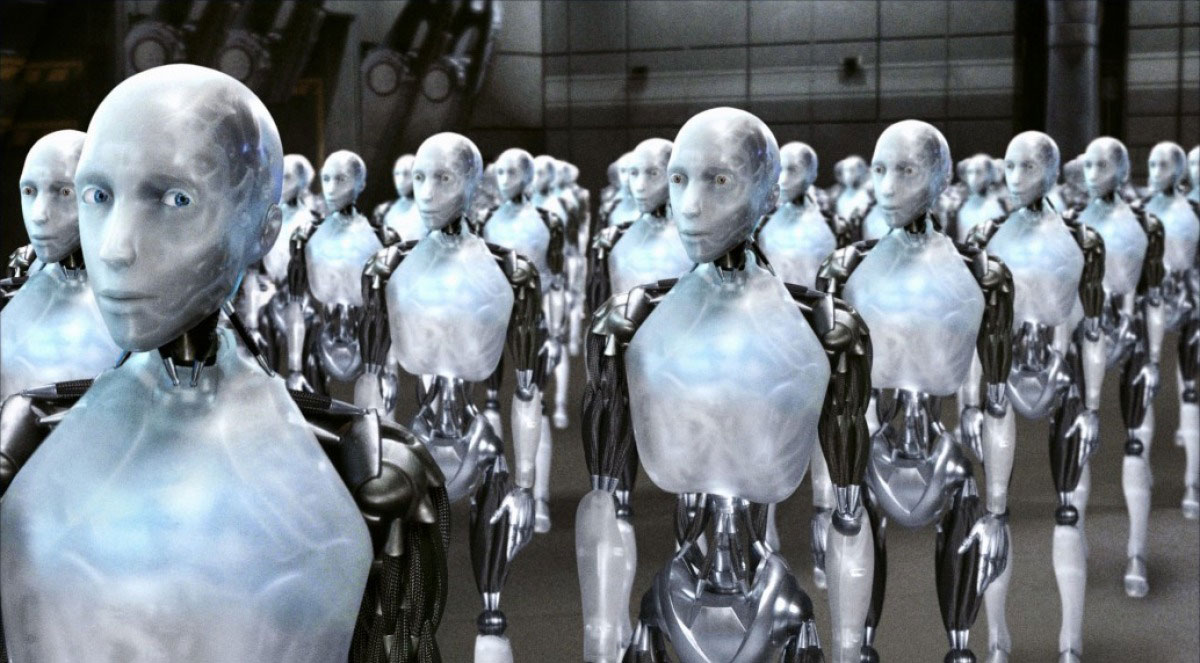

Noah Kadner: Though virtual production may be a relatively new concept to many today, it has its roots in motion capture in movies like Avatar. But before that movie came efforts to showcase digital anthropomorphic characters, such as Proya’s 2004 film, I Robot.

Alex Proyas: There was very little motion capture in that film. we shot with our actor in a green suit on the floor as we were shooting, Alan Tudyk, who plays Sonny, the character of the robot in I Robot, was there for the entire time, working opposite will. And sometimes, he would shoot claim plates to remove him. Other times we would paint him out somehow, pain was experienced to remove him from certain scenes, and then of course, his. performance was captured. It was keyframe animation. Digital Domain and Weta as well. Did some work on the film, and I’d go in and watch their first animation run, which was the grayscale robot on one side of the shot of the frame.

And on the other side, there would be Alan, in his fetching green leotard, and it was all about capturing performance to the most minute detail. So I’d be, in there going no, his nose flares on frame 14. Can you make it more like that?

He goes, it goes a little further. And this goes right down to body movement as well. It was like a rotor scoping process, almost where we tried to capture the soul of the performance. And I think they did a very good job doing it. And in some ways, it was almost better than tracking markers on the face and all that sort of stuff.

Because of it, he could do the performance unencumbered by motion capture suits, and also it allowed us to work faster on the shoot. We didn’t have to set it up. Motion capture volumes for every scene that we had the robots in. So it was one less technicality to deal with when we were shooting.

So yeah, the technology supported that way of working well at the time, but the other thing about I Robot, but that’s really significant, is that we were one of the first films to use virtual production, Where all this stuff came from is not Mandalorian is a lot of people believe, but been doing it for a long time.

It’s just Unreal Engine and real-time. Led screens and all that sort of stuff. That’s what’s happening now, which is making it more user-friendly. But, we did one of the first scenes. Certainly, one of the first things I was involved with, and I believe one of the very first scenes overall that we did with this, was an item called encodacam, which was a way for you to see Will Smith running around a green world.

move my physical camera around, which we’re still filming those days. And, see on a monitor a very crude CG model that is being driven by the physical camera, with all the little robots, all the thousand robots where he’s running around through. So then I could see.

If I drop the camera a little bit, I’m going to lose him behind all the robots, or if I go through, and he’s walking at a certain pace, I’ll see him in the distance, and he was really the only way to achieve that scene. there is no other way we could have done that scene without those techniques, short of building a thousand styrofoam robots or a thousand C stands with ping pong balls on them or whatever, this is by far the best way of doing it,

Noah Kadner: Proyas continued his steps into the virtual world with Gods of Egypt, a project that would have significantly benefitted from LED volume virtual production. But at the time of the project, the technology did not yet exist.

Alex Proyas: the film was almost entirely green screen. there’s very little traditional photography when there is anything, traditionally, it was on a set. there aren’t many scenes where we don’t have the entire world created. So I don’t know, maybe 85, 90% of the film is entirely virtual.

We did bits of sets that we extended in some scenes, usually anything that the actors have physical interaction with, obviously any furniture that they sit on or whatever constructed, but there’s very little that wasn’t touched in some way by virtual production on that.

We built our set pieces across multiple stages. Here in Sydney and it’s not like now you can almost bring everything to one volume and not physically move your unit. So tracking and everything is all in situ, and it’s all worked out and calibrated, and you simply bring your set pieces in and change the environment. in those days, we would hop from set to set.

We got through the production one way or the other. and, there were many scenes where the virtual was helpful, and it certainly was helpful, in terms of being able to edit with something other than a green screen turn black or whatever, which is a horrible way to edit a film because.

You don’t get a sense of the flavor and the atmosphere, and you got to try and just focus on the actors, and that’s it, and obviously, the world creates so much more, can improve performance, if it’s done properly, so that was my experience there.

And, of course, just a few years later, the hardware and the software have gotten so much better. That is what we’re doing now, we can, even when wrong green, we walk away with footage that is, you see everything, you see the quality of the light in the environment.

I was saying, 10 years ago, if it was a kids’ TV show, that would be it. That would be the finished version. it would be even better than what they were doing in those days. but then taking that and finessing it, of course, is what gives you the best photo, real result,

Noah Kadner: With his extensive experience in traditional visual effects, Proyas is in a well-informed position to evaluate the best ways to leverage virtual production.

Alex Proyas: Green screen and LED, they both have their pluses and minuses. green screen does certain things really well and other things not so well. And LED also has its merits and downside. And one of the things that are really great at, I think, is if you’ve got your environment to be exactly what you want it to be, and it’s working really well, and particularly on, closest shop. Where you don’t see the actors connecting to the ground, et cetera, it’s fantastic.

You can do a lot of your coverage leg, but then when you come to your wide shots, and you want your actors to physically move through an environment or just sit wide on something spectacular Vista or whatever, grain tends to be preferable on Gods of Egypt, we did a lot of, virtual environmental replacement outside, which is also a very, powerful tool.

When you’re doing daylight, exterior studios are not the best place to be to reproduce hard sunlight. when your actors are moving over a great area, the way we tend to do it, if the actors are running in some sort of action scene with daylight, we want them to be in daylight.

We usually put them on a treadmill. So you get that hard source of light in that focused area, that if you’ve got action over a big area, and there are multiple characters all moving around the stage, there’s a reason why a lot of. The LED stuff, the Mandalorian, et cetera, it’s overcast weather or dawn or dusk or whatever, because that’s what LEDs are really great at doing.

It’s the VFX story from day one. It’s working out your shot, storyboard your shot, And then work out where the best technique is to do it, that hasn’t changed, nor will it ever change, depending on what the shot or the sequence or the film production dictator, we mix it all up and sometimes we’ll get. You know what nothing’s going to be the real world, and we can do it. Let’s go shoot it for real and add stuff to it, expand the environment out, et cetera, et cetera.

Noah Kadner: Proyas sees LED volumes as a stepping stone to more and more interactive ways to experience entertainment.

Alex Proyas: I honestly think. It’s an ever-shifting, ever-evolving process. Until you can stick something into the back of your head as a creator and dream film, and out it comes, there’s no endpoint.

There are a lot of steps before that, of course, think we are moving more and more towards fully CG creations. to me, that’s a no-brainer right now, we’re making the interface between live action and virtually seamless, the real-time approach in LED screens and green screens.

Yeah. making it more user-friendly, easier to apply to any number of projects, and more affordable, which is a really important part of it. One of the reasons I built my company is to democratize this sort of. So you don’t have to be ILM and Disney to pay for it. we’ve just finished an indie film it’s about $6, or $7 million, and it’s entirely virtual, and for me, that’s a huge success story because the main reason I want to do all this stuff is to allow filmmakers creators to do whatever they want, not limit their imagination.

So the first time we’re making a film is an art form, like writing a book or writing a pace for an orchestra or symphony, you don’t ever think really about the logistics you don’t limit your imagination by budgetary concerns when you’re writing a great novel. And so finally, I hope we’re getting towards that point with filmmakers where they can do them. in the same ways, other artists can, and that frees them from the tyranny of studio investments.

It’s, there are all sorts of great stuff that comes out of that, and we’re starting to see the tip of that iceberg right now, I had a film that I was making that didn’t happen, a film based on Milton’s Paradise Lost. Around 2010, which basically fell over because we’re going to do it all completely CG effectively.

And it was real state-of-the-art stuff that was being achieved at the time, but the budget kept going north, and eventually, this year went enough. We can’t support this any longer. And, now that same film, I could probably make four. Maybe a quarter of what the budget was, and to me, that’s great. It means that projects that are really out there both conceptually and technically can be achieved now, so I think that’s a really important part of all this, the moment this stuff becomes cheaper and better, everyone is going to do it, and that’s what we’re seeing in the virtual production space right now is every TV show is starting to adopt and every sci-fi TV show, but eventually it’s gonna. Not just sci-fi and fantasy worlds.

It’s going to become when it’s cheaper and easier to shoot your domestic drama or whatever you’re doing. Rather than moving your unit around town, staying in one volume and pressing a button and up comes your room, your card, or whatever. and it’s seamless, then everyone’s going to be using that technique, technical progress, yes. The LED screens can get better. the contrast range can improve. A lot of technical things can improve. And they are improving. And the more we do, the more practitioners use these techniques, and more improvements are going to be made.

Noah Kadner: Asked how newcomers interested in virtual production can get into the business, Proyas points to the ever-widening talent gap fueled by the strong interest in LED volumes and real-time animation.

Alex Proyas: We’re struggling in Australia. Getting artists involved with these techniques, these new techniques, which in the VFX industry was a struggle at the best of times. But now, with this huge level of interest in this space to find enough practitioners who understand these new, applications, it’s a struggle we’re already talking to, educational facilities and a university here in Sydney about setting up a program to train filmmakers and don’t see. Diminishing, I think that’s going to keep expanding and we’re going to need more and more people to keep up with it, cause again, as these techniques become more used and filmmakers’ imaginations can flourish. And there’s more and more interest in those science fiction, fantasy worlds, et cetera.

More content will need to be created. Therefore more filmmakers will need to be engaged, so I think, getting into that area of expertise, knowing all the software, that we use I like people who are consummate filmmakers or people who are even very junior people who are working with us. They’re interested in not just doing comps with nuke or something, their interest is far greater. They take a very active interest in the shooting of the stuff, as well as the editing, as well as the writing is everything, So my advice, I think to filmmakers is to take that active interest.

Because it’s all coming together, the whole thing with Heretic Foundation, my company was, it was conceived as a soup to nuts kind of production entity. It’s not just VFX. It’s the whole gamut of production. And at the moment, we’re negotiating with some investors to build a very large stage facility, but it’s not just going to be an LED volume and a green screen volume. It’s going to be editing rooms, sound rooms, a sound mixing suite, a DBI suite, the whole thing, so all these people, all these different levels of expertise are all going to be in the one space. I hope in the same physical space because who knows what pandemics are awaiting? but I hope we can all be there together and all feeding off each other and all making that spine of virtual production more and more streamlined and efficient.

The more, about the whole process, in today’s filmmaking world, I think the better you are to be able to serve your chosen task,

Noah Kadner: You’ve been listening to the virtual production podcast. Special thanks to my guest, Alex Proyas.

Leave a Reply