Amazon Studios’ Fallout: An Expanded Interview with Virtual Production Supervisor Kathryn Brillhart

Virtual production has emerged as a game-changer in filmmaking, blurring the lines between virtual and physical filmmaking. The Amazon Prime Video series Fallout, a post-apocalyptic thriller, has captivated audiences with its world-building and cutting-edge visuals. We had the opportunity to sit down with the show’s virtual production supervisor, Kathryn Brillhart, to discover the methods behind this production.

When did you become involved in Fallout, and what role did you play in the show’s virtual production?

AJ Scuitto, Magnopus’ head of virtual production, brought me into creative conversations early in 2021 alongside the Magnopus team to help pioneer the role and institute best practices from the ground up. At that time, I had just wrapped production on Warner Bros’ Black Adam, completed prep for Netflix’s Rebel Moon and worked with John Dykstra on an R&D project commissioning the Universal Studios VP Stage when I got the call that Fallout might be moving forward.

With my background as a cinematographer, experience in running camera and lighting departments, and work in post-VFX as both a Producer and an indie VFX Supervisor, this project was particularly attractive to me. When I met with AJ, I remember saying, “I don’t know exactly who is responsible for the virtual production shots in Westworld, but I’m trying to track them down, and I want to work with them.” It turned out that it was Magnopus, and they were looking for a Virtual Production Supervisor to pair with their team on Fallout. We shared a similar vision for how to set up a project and cast roles with intention.

- Virtual Production (particularly on a complex project) should be a separate department and budget from Visual Effects.

- The VP Department should have an executive producer (AJ), a VP Producer, and a VP Supervisor working together to manage the team’s day-to-day operations.

- Our department leads should be able to connect directly with each department and have a communication strategy so that we can operate as a fully functional client-side team supporting the director and department heads.

What was your role as VP Supervisor?

One of my objectives was to create space for our team and partners to prep together and in parallel. Uniquely, a virtual production team plays a supporting and partnership role with other departments as the crew prepares and moves toward production.

It was essential to have strong department leads and mini teams that specialized in crucial aspects of the process, i.e., visualization, VAD, matte painting, lighting, camera/object tracking, engineering, FX, volume control, fabrication, networking and more.

From prep to production, I helped bridge communication between these groups, our partners, and production. Additionally, I worked with AJ to ensure any major shifts in methodology or team structure were communicated to production and aligned with both Magnopus and production’s needs. Building rapport with certain team members on past projects helped us have more of a shorthand going into this project.

What were some of the key technical hurdles?

From a technical standpoint, shooting Fallout on film required a unique color management workflow that would need to be accurate, from our content creation pipeline to the LED wall to the film camera. I developed a methodology for using a digital reference camera, applying the LUT and additional color measurement tools to achieve this goal, which we refined throughout shooting.

Why use virtual production vs. more traditional methods?

One remarkable aspect of working with this creative team was their intentional selection of scenes and environments for in-camera VFX. They chose four key environments: the farm and vault door scenes in Vault 33, the cafeteria scene in Vault 4, and the New California Republic’s base inside the Griffith Observatory. Additionally, any shots inside the Vertibird were designated as LED process shots.

These environments represented a small percentage of the series overall, and one of the learning curves for production was the extra time the director needed to dedicate at the beginning of the prep process, such as time invested in virtual scouting, creative review sessions, and test days. Our team constantly visualized and demonstrated how these shoot days would work with accurate measurements and team input. The VAD team continually communicated with production design, helping ensure the virtual and physical sets would integrate. Once the team adjusted to the process, we developed a rhythm and flow that fit into production’s weekly prep schedules.

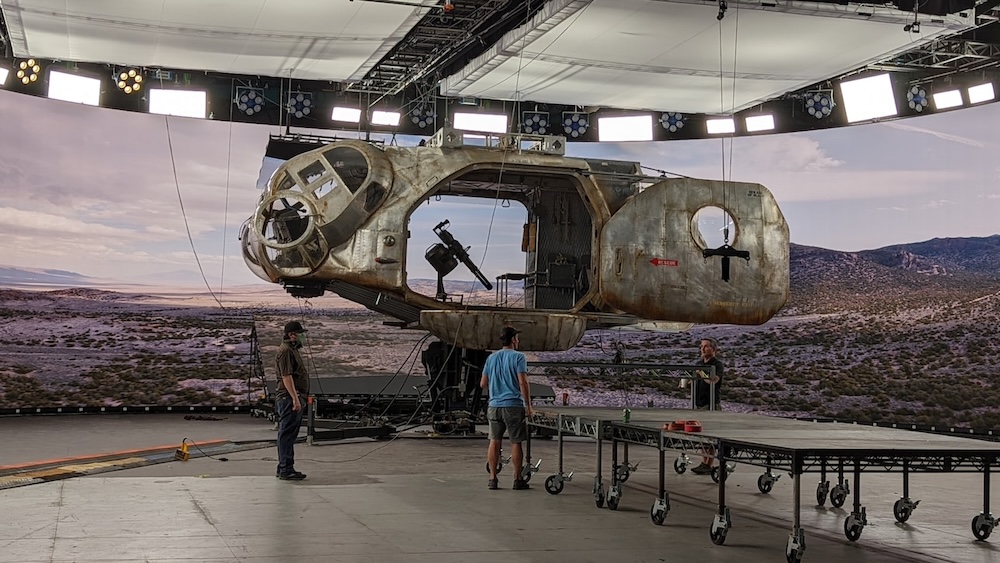

Talk about the form of the LED volume itself.

We were very lucky to design a custom horseshoe-shaped LED wall with Fuse Technical Group within the MBS Studios stage in Bethpage, NY, that would complement each environment designed for the show. Up to seven 6 x 9’ LED wild walls were outfitted with a Stype Spider object tracking system, which allowed our team to patch content at the correct perspective as needed for VFX or the DP for interactive lighting.

Our visualization team was critical in helping estimate placements to plan ahead with grip, lighting, and Fuse’s engineering team. During the first block of shooting, they were most prominently used in the Vault 33 doorway scene and Vertibird shots as tools to continue the set extensions beyond the edge of our wall to avoid seeing the stage floor. We could also raise the smaller panel sections into the ceiling if needed for image-based lighting. Having an open ceiling meant that our DP and Gaffer could design lighting with more control, giving stunts more flexibility.

How did the team collaborate?

Early on, we set up a direct two-way communication path between VAD and production design to ensure both parties could ask questions, send files, and share design details. Our visualization team was also involved with each department, often providing sessions focused on equal parts story and technical strategy. In our master schedule, I laid out a plan for the reviews our team would need with the director and individual department heads. Those requests were submitted early on and regularly so that production could plan them around the other department meetings and scouts on the schedule.

The creative sessions helped us work out logistics together, and we would often set up break-out sessions for department heads to brainstorm ideas. Facilitating real-time collaboration and integration greatly benefited each sequence we worked on, and each one has its own unique case study.

The vault door scene (where Lucy exits Vault 33) is one example because each department head could see precisely where the physical set and virtual set extensions began and ended. Individual departments could draft ideas with our team leads, Kaylan Ray, Craig Barron, Katherine Harris, Devon Mathis, and Jeremy Vickery. These small sessions helped prep for larger group calls with multiple departments and sessions with the director. Working in real-time with CG environments is essential because we can all simultaneously experience virtual prep in a kinetic way. Virtual scouting sessions allowed us to work with spatially accurate content, interactive light, and moveable set pieces.

As an example, in every environment, the director wanted to be able to place cameras anywhere they needed to on the day. Our VP team could communicate where we would have the most optimal camera tracking early so that the DP and director understood the space they could work in. It also helped them push the limits of what was possible before physical production so that our team could prepare for extremes, including the ability to machine custom parts and camera mods to improve the tech on the fly and adapt.

Did VP enable the filmmakers to explore any unique ways to create shots?

Vehicle process shots, such as our Vertibird scenes, proved to be ideal use cases for working with photorealistic imagery. Instead of figuring out how to engineer a working Vertibird with supporting in-camera VFX, we were able to help bring that physical set piece to life with 2D plate photography and interactive lighting. This allowed actors and the camera department to capture dramatic performances inside the Vertibird influenced and lit by the world of the scene.

The scenes inside the vault farm were also great examples of this because the script called for the characters to live in a world where they accepted a ‘projected reality’ as part of their own world. This allowed the design of the content to be part of the plot, down to the film burn effect and the standby screen.

In episode one, there is a community meeting that takes place after the Raiders attack. That scene was shot entirely on the volume. The coverage that looks into the ‘stand by’ screen and the reverse with the vault’s architecture were shot in the volume. Our team used photogrammetry to capture the physical set in Brooklyn and recreated a virtual 2.5D version of the set in Unreal Engine. This allowed us to create just enough parallax to sell the shots. Our ability to work with the gaffer to capture his lighting set-up and fine-tune it live on set also improved its integration.

The farm scenes were also a unique challenge in that they required designing a stylistic set extension that would need to integrate with physical, photorealistic set pieces at multiple times of the day. Because the script called for a projected landscape that would extend the depth of the farm and cornfields, this made matte paintings an ideal solution. The challenge was designing the visual transitions between the 2D matte paintings, 3D corn, and physical corn. In a technical sense, we needed to match the color and perspective of the corn and have the parallax read accurately to the viewer. From a story perspective, we needed to make sure that the overall look matched the tone of the scenes and could be believable to the characters living in the vault.

Then, from a mechanical perspective, we needed to make sure that elements like the film burn or the stand-by screen appeared more photorealistic to sell the effect to the viewing audience watching the show. When the film projector’s beam burns the film, we see that the deterioration of the film affects how it catches in the gate, causing increasing jitter separating elements of the image. When the wedding celebration transitions from sunset to nighttime, it is believable in the film world and happens live mechanically on set. These moments made the story and technology work in harmony with each other.

Can you give more details about the Vault 33 doorway scene?

Lucy experiences a pivotal moment when she leaves the vault for the first time. Working with LED set extensions meant that the team did not have to location scout an underground bunker and try to figure out crew logistics in a predetermined space on location. Instead, Our production designer could design the area and capture most set extensions in-camera. The size of the stage gave our production team the depth of space needed to frame shots with actors at the proper scale.

It also meant that when shooting the reverse angles as Lucy looks back at the vault dwellers she is leaving behind, there was enough separation between the lighting set up by the DP to cast appropriately on the physical actors but not hit the LED wall. When we see the vault door shadow and light moving across the back of the vault room, it’s our 3D unreal engine environment built out with proper matching lighting and an animated shadow of the vault door. Our team timed the effect in person and executed it live for the camera.

Bringing these creative elements to life took our entire team. Everyone on the crew owned a piece of the process, and was essential to its success!

What were some of your key insights gained during the production?

It is important to cast your team with diverse skill sets that overlap. This is essential for the flexibility needed when supporting a director’s vision and user experience, as well as scaling the team.

When managing color, whether for digital or film capture, figure out exactly which parts of the workflow you need to be able to adjust and fine-tune early in the process. Once your tools are in place, develop a methodology for who will make the adjustments, at which point in the pipeline, and how. Just because you can adjust something doesn’t mean you should.

For example, if you are working with Steadicam on an LED volume, incorporate the operator into the prep process. Often, they need to be given adequate time to prep for the additional balancing, hardware attachments, and possible genlock cabling they will need to account for. And all of this certainly varies depending on the hardware ecosystem you are working in. I was fortunate to be connected with Chris Harhoff at least a month before he arrived on set so that he had enough lead time to prep, ask questions, and get support from our team.

How do you see virtual production evolving, and what excites you most about its potential?

Virtual production is an evolving discipline that involves many more techniques and workflows beyond LED walls and in-camera visual effects. It also opens up the possibility of bringing physical filmmaking workflows to fully CG projects, whether they are pre-rendered or rendered in real time. These techniques are lowering the barrier of entry to traditional visual effects and making it possible for filmmakers to explore workflows they might not have had access to otherwise.

This is also true regarding integrating machine learning and GenAI workflows into filmmaking. Both real-time and AI are tools that can improve existing workflows, including virtual production. However, they are both budding art forms with their own paths to distribution. Virtual production techniques play a role in helping the art of filmmaking adapt to the new technological landscape that we are entering.

What advice would you give aspiring virtual production professionals?

Understanding the origins of tools and techniques is always helpful, but following your passion for creativity and the process is the best way to dive in. With technology advancing so rapidly, you can start anywhere! For example, if you’re starting in physical production, these tools can help you get closer to visual effects and CG workflows. And the opposite is true if you have started as an engineer or visual effects artist. Since real-time rendering is at the heart of this movement, I suggest getting hands-on experience with game engines to become familiar with how they work.

If you haven’t seen Fallout yet, you owe yourself a look. It’s an incredible show and a great showcase of Virtual Production. For more from Kathryn, check out our live Virtual Producer episode here:

Leave a Reply